For most Americans, being hospitalized is a rare and frightening event. Trips to the emergency room, or even for an out-patient procedure, are draining, and too often the experience is made worse when patients are left with unexpected bills. Now, hospitals are adding to that burden by raising prices — and it’s not because they’re improving care.

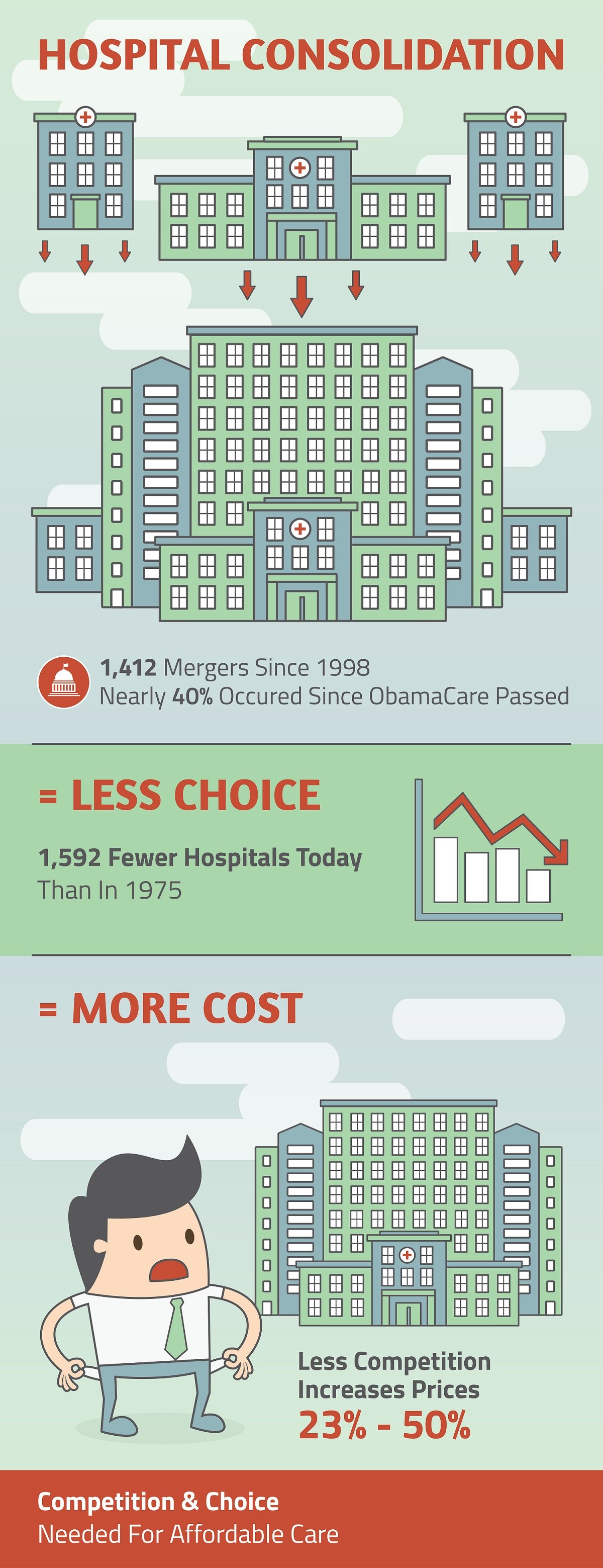

Hospital systems across the country are consolidating, incentivized in part by Obamacare regulations, which encouraged hospitals and physicians to work together in “accountable care organizations” — an effort to tie cost to quality control metrics. As a result, large hospital groups have bought smaller hospitals and private physicians’ offices, often closing down facilities in the process.

Since 2014, the American Hospital Association reported the loss of nearly 170 hospitals nationwide. And there’s no sign this trend is slowing. Kaufman Hall, a management consulting firm, reports that 29 new hospital consolidations were announced in the third quarter of 2017 alone. Investors like these mergers. Private equity continues to flood into the industry, especially into the for-profit health system.

On the surface, there is nothing wrong with these mergers. Economies of scale can drive up efficiency, lower costs, and ultimately provide a better experience for the patient. But economies of scale and hospital consolidation only work if there’s also competition. Without competition, there is no incentive to lower costs or improve quality of care. And that’s exactly the problem patients are running up against in our current climate of consolidation, in which patients now face higher prices and fewer choices.

Similarly, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that hospital consolidation can lead to a price increase of more than 20 percent. Consistent with that is research by Zack Cooper, Assistant Professor of Public Health at Yale University, who found that hospital monopolies typically charge prices more than 15 percent higher than hospitals in markets with four or more competitors.

None of this is surprising. When there’s no competition, there are fewer incentives to control costs and quality of care. And patients are left with no other option but to accept the inflated costs.

Washington — which is to blame for setting this merry-go-round in motion — has recently begun to wake up to the threats associated with hospital consolidation. A few years back, a judge in Massachusetts put the brakes on a merger of PartnersHealthCare, which owns the suite of 10 hospitals affiliated with Harvard, with three additional hospitals, noting the threat of price gouging. And this year, the Federal Trade Commission stopped the merger of Advocate Health Care and NorthShore in Chicago, also citing a lack of competition and the concerns over price increases.

Government interference through the Affordable Care Act may have given hospitals an excuse to consolidate, but rising profit margins and diminishing competition means they have little incentive to improve their operations. Putting patients first — and really driving down costs in health care — means we need to consider the danger of hospital monopolies.

Matthew Kandrach is president of Consumer Action for a Strong Economy (CASE), a free-market oriented consumer advocacy organization.